How do people really learn? As an instructional designer or learning and development professional, understanding how people learn helps you deliver training that hits the nail on the head.

It’s more complicated than learning styles or picking video over written instructions. In fact, there’s a whole science behind it.

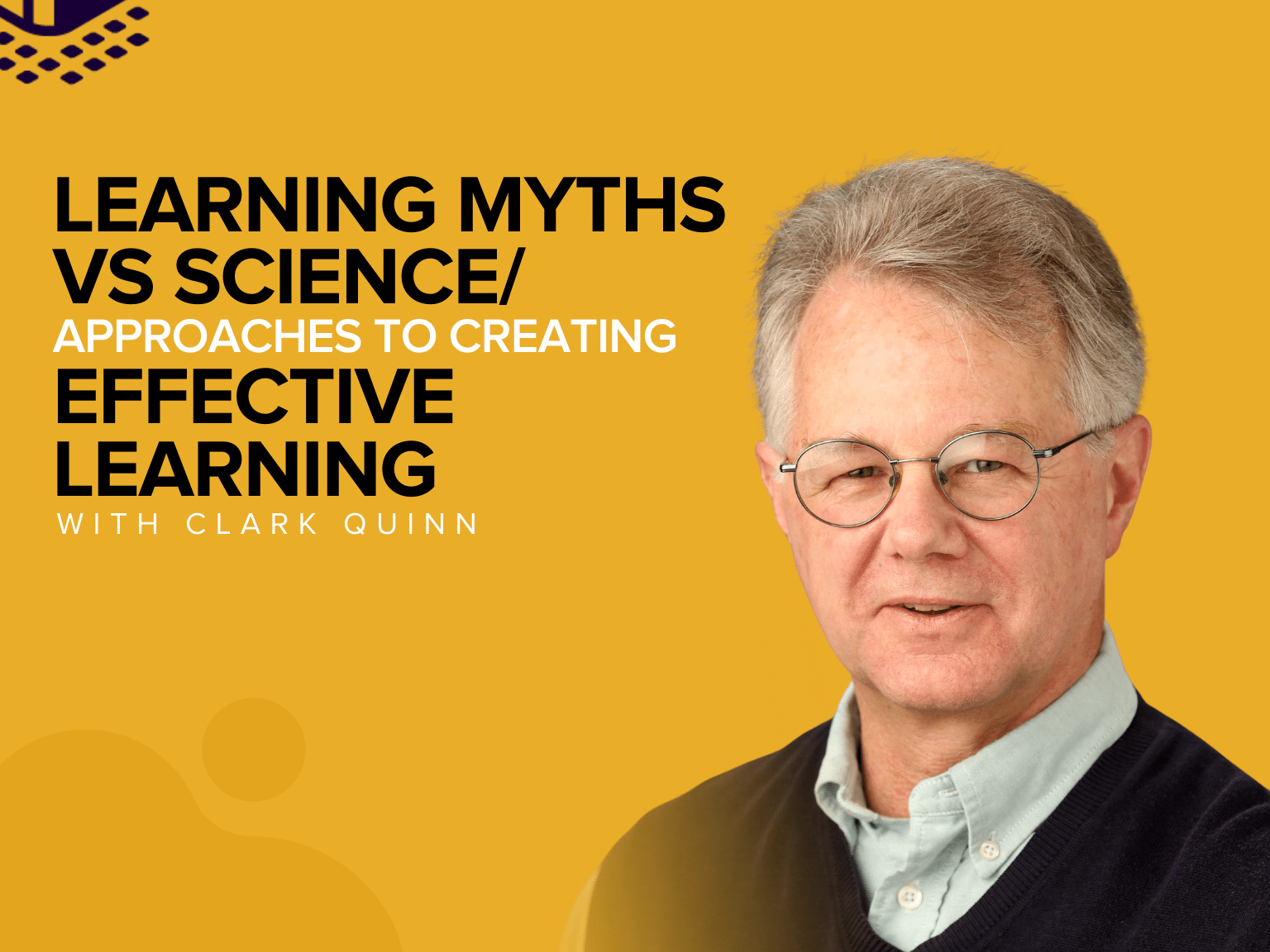

Clark Quinn, Executive Director of Quinnovation, joins this episode of The Visual Lounge to impart some words of wisdom and share his knowledge on the science of learning. He takes us through what the research shows and busts some common myths we could all do with putting to bed.

Clark provides learning experience design strategies for corporations, higher education, government, and not-for-profit organizations. He’s an award-winning consultant, an internationally known speaker, and author of six books.

He integrates a deep understanding of thinking and learning with technology to improve organizational execution, innovation, and ultimately performance.

What is learning science?

For those unfamiliar with the term, Clark breaks it down simply as the scientific study of how we learn. While that might seem obvious, it’s a field that has until recently been under-explored.

It all started when people realized that philosophers, linguists, neuroscientists, and psychologists all had valuable knowledge of the human brain but were just not sharing it with each other. This led to the formation of the Cognitive Science Society in the early 80s.

After that, another group of people affiliated started looking into the study of learning, and in the early 90s, they created the International Society of the Learning Sciences. Essentially, it’s a cross-disciplinary view of learning.

Why it matters to businesses and workplaces

Many businesses rely on learning styles and personality tests to figure out the best ways to train people. The problem here is that a lot of these are built on assumptions, not research, says Clark. He’d even go as far as to say a lot of it is down to “snake oil” tactics and made up.

By understanding how learning works, it saves you from spending money on snake oil, and gives you a higher chance of success.

“The old model of the brain was that we’re these logical, reasoning beings. And therefore, if we give us new information in bullet points and stuff, this will change the way we behave. And it turns out, that’s just so wrong. So you really need to understand learning science.”

What you need to know about learning science

If everything you’ve believed about learning is wrong, then where do we go from here? Clark shares a few things you need to know about learning science.

The first thing to know is that our brains operate on a neural level, but that’s not a useful level in this case. The right way to think about it is through a cognitive level.

The cognitive approach is about perception, sensation, and attention and how that gets into the working memory before making its way into the long-term memory. That is, as Clark explains, learning in a nutshell. Understanding that core process is where you start.

The next thing to think about is how you apply knowledge and make better decisions with it. For that, you need practice. Practice is what will transport that knowledge into the long-term memory.

What will make a difference to your organization is avoiding the type of learning that results in a team of people just reciting facts. Reciting facts is not real learning.

According to Clark, real learning results in better decision-making, which leads to organizational success.

Why minimal information is best…with context

Generally, less is more when it comes to knowledge transfer. Providing minimal information during training is better because anything more can add to cognitive load.

Diving deeper, Clark highlights that it’s not just about the amount of information. It’s about context as well.

Abstract problems are usually harder to understand. It’s tougher to learn and process abstract things without valuable context. Putting abstracts into a contextualized setting goes a long way in helping people understand them better.

“We shouldn’t just ask multiple-choice questions to ask for recall. We should put it in the form of a little story that they have to respond to, that we can dress up with context that gets processed pretty much subconsciously. And so, it’s not interfering with our cognitive load.”

It’s a delicate balance. You want context, but not so much that it distracts or adds to cognitive load.

“You don’t want stuff that requires additional processing on top of the learning processing, because you should be designing the challenge in the learning task to be difficult enough that they don’t need any additional challenge.”

The problem with learning style myths

Are you a visual learner or an auditory learner? Do you know your personality type?

There’s a good chance you’ve done one of these tests before. The problem is that people put way too much stock in them when there’s little evidence to back them up.

Clark highlights a few problems with this. It can waste time and effort. It can waste money, but it can also be damaging. It undermines our learning effectiveness and limits us.

If you believe you’re only a visual learner, you might be deterred from other types of media you could benefit from.

“It’s so much more individual. Our brains like to categorize things, but it isn’t always helpful. Sometimes these simplifications are on a false basis and lead us down the wrong tracks.”

Simplifying learning in this way is definitely appealing. It’s easier to understand and categorize. But it looks like there’s no real benefit to designing a training program for visual learners specifically, for example.

However, there are benefits to multimedia methods of delivering content. Video, in particular, is a flexible medium that provides dynamic context – making it ideal for learning. But it’s also important to mix it up and provide a variety of mediums when designing training content. Variety can help boost attention and engagement.

“Trying specifically to design for different learning styles isn’t useful and is, therefore, a waste of resources, instead of saying, how do we use the media appropriately to meet our learning goals?”

Why learning design professionals should know learning science

Clark sees this as a professional obligation. You don’t need a Ph.D. in learning science but making an effort to really understand the science and research behind learning should be on everyone’s to-do list.

“Just as you expect your plumber to understand the properties of pipes or your doctor to understand the properties of the body, we should understand learning if we’re going to be doing this responsibly.”

If you want to start your own research on learning science, Clark recommends seeking out primary sources for academic journals on the subject. A couple of books he recommends are ‘Brain Rules, Updated and Expanded: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School’ by John Medina and ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ by Daniel Kahneman.

For more tips on instructional design and video creation, check out TechSmith Academy in the meantime.

Share